From point A to B. How did the Dutch language (or most Germanic languages) get their names for their mishmash of ways ?

In the lowlands most villages were named after their geo locations. Since villages/communities rose near water sources, most names can be retraced to Celtic, Germanic or Roman words for marshlands, shallow area to cross river, elevated area next to river, and the likes. Depending on when a village was founded or recognized. The same suffixes may pop up in different regions. For example Woensdrecht and Maastricht both were founded because you could (often) safely cross the river at that point. However these are located in opposite ends of the Netherlands. Maastricht was a placed to cross the river Meuse and Woensdrecht to cross the Scheldt and (most probably but debated) refers to Germanic god Wodan. Like Wednesday in English is Woensdag in Dutch and both are presumed to be dedicated to the Germanic deity.

The -trecht, -tricht,- drecht, -dracht always refer to the same. Dozens of such suffixes exist.

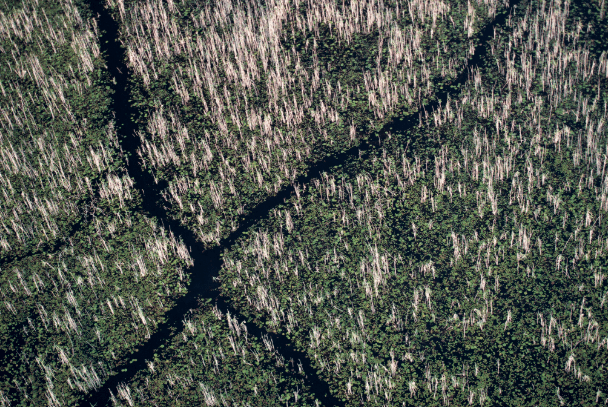

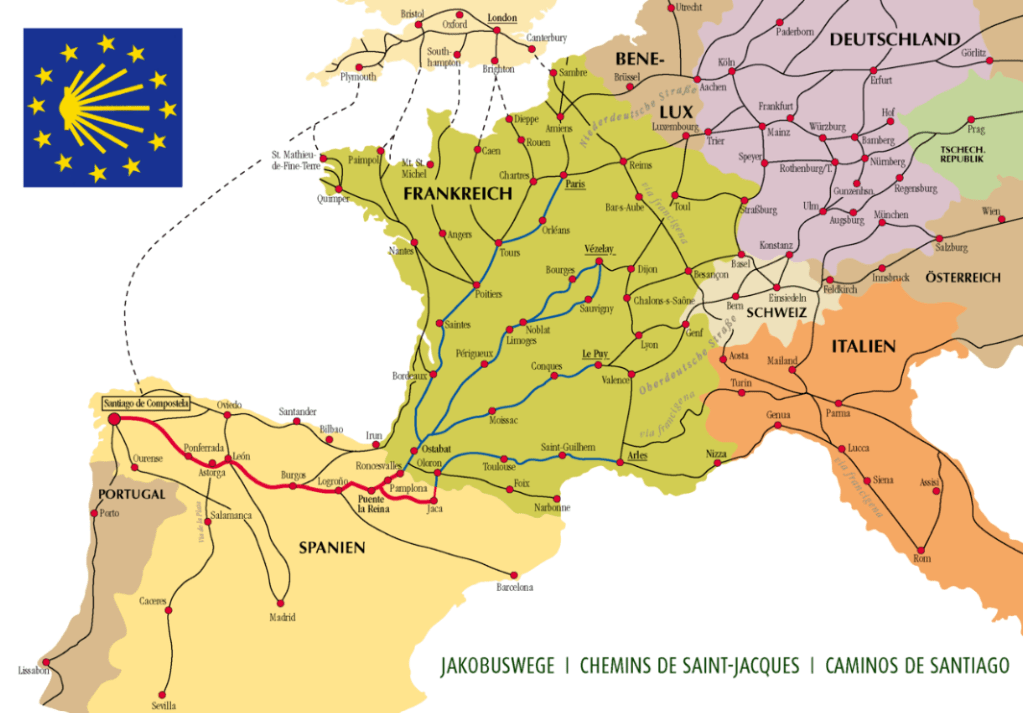

To link up communities paths were created. Please note that these paths were created long before the Roman era or even before the invention of the wheel.

I have to admit that my region was not continuously inhabited because of the nearby river Scheldt. Frequent flooding made the area too dangerous to live. And people were not forced to live where danger lurked. Some people do live voluntarily in dangerous areas, like Naples (Pompeii is nearby), since the soil is very rich and their fruit and vegetables very tasty.

Basically all of current Belgium and Southern part of The Netherlands were largely ignored due to (often infertile) marshlands for quite some time.

Road: from Proto-Germanic raido and basically from ‘riding’. In Dutch we don’t use this word or derivations. In Dutch “baan” is the most accurate equivalent in the meaning of free/safe passage. The Dutch language has a saying “zich een weg banen” meaning to create/pave a way. No direct translation there unfortunately.

Also in sports the Dutch language use “baan” like a sports field/court in tennis, cycling, ice-skating, gof, etc. The Dutch also use “baan” for a job and that comes from ice skaters that preferred ice rinks because they were too scared of natural ice. When they went to skate/ride on the ice “baan“, the term “baantje trekken” was used. In Dutch maritime jargon “baantje” (lit: little job) was applied for less strenuous and tiring tasks aboard a ship. Nowadays job and “baan” are synonyms.

Boulevard: is an important and broad street derived from, ah oui, la France. However a Middle Dutch word the French bastardized “bolwerk“, yes, recognize bulwark. Initially it meant a fortress. The French appropriated the word and expanded the meaning to include the pathways on the ramparts of the fortress. In the second half of the 18th century the French created those monumental, broad roads towards Paris city center and called them boulevards. The Dutch in turn now also use the the word to describe a road. Obviously the Dutch no longer understand the link between their “bolwerk” and boulevard.

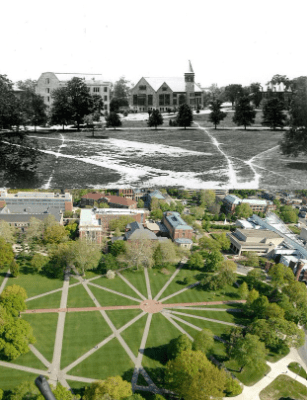

Drive: a broad, rural road. Originally a road where cattle was driven. Originally from Old High German. In Dutch language we use “dreef“, hence the broader nature of these paths. A Dutch expression goes: “op dreef zijn“, like ‘on the road’ or literally droving meaning you are doing well; or doing a great job. Are you already seeing a pattern?

Canal: Not sure if an accurate English word exists. In Dutch the path next to the canal is called “gracht“. It is closely related to the English grave or Dutch “graven” (to dig). Just like boulevard, the meaning got expanded in this instance to the pathway next to canal. Dutch city Delft is derived from “delven” a synonym of “graven”. If you have visited Amsterdam you will be aware the streets next to the canals have the exact same name (ie Prinsengracht – Prince’s Canal). I would advise not to walk on the wet part of the canal even when overly confident on substances.

Towpath: is related but not exactly the same. In Dutch we call these “jaagpad”. In Dutch you might be confused as we use “jagen” which can also mean to hunt. However in Dutch “jagen” also means to push/pull something like cattle or peat boats.

Court: Original meaning in Dutch is an enclosed area, like the English manors or estates. The Dutch word “hof” has many meanings. Anyone surprised since the word is in use for more than 1000 years? Enclosed area, garden, residence, etc are just a few examples but we also use it for cemetery as ‘church garden’ (kerkhof) or labyrinth as ‘wander garden’ (doolhof). The Dutch meaning and US/UK meaning differ. In the lowlands the court is always fenced off. Usually old castles, manors or estates that have public pathways; be aware some areas are not always public domain (please do respect that so the publicly accessible paths remain public). The best well-known “hof” in the Netherlands is “Keukenhof” but be aware this not a public area (entrance fee).

Quay: like Dutch “kade” (verbally “kaai” is more used) means way on embankment/riverside/levee. it is derived from Celtic word for seperation, enclosure and the Dutch equal to “haag“. Over time the meaning has shifted towards loading/unloading area in port. (photo: Bergen op Zoom)

Lane: “laan“, way with trees. Etymology is unclear. Might be from Greek word to tow: “elaúnen“. In that case a lane is a drive or vice versa. In Middle Dutch a lane was a side road, linking up a destination from the main road. I assume that makes it more a driveway. That is how you knew you were on someone’s property, a single line of trees on both sides next to a path. Our modern concept of road with trees is not even that old. When I say not that old, I mean not more than 1000 years, just as context “when a European says not that old”.

Path: pad, small way. Obviously this one is one of the oldest and less easiest to find the origins. Certain is that Germanic languages, Greek, Sanskrit, Persian and others have similar words. Perhaps noteworthy that in Dutch language “wandelpad” (hiking path) is used due to many meanings of the word “pad“. Like toad or Thai dish or even the English meanings for pad have invaded our language.

Place: “plaats” loan word from Old French “place“, which means spot or area. From Latin “platea” broad street or courtyard, which was taken from Greek “plateia” flat, broad and spacious. A place is literally a flat area/space. (photo of Groenplaats, Antwerp)

Plain (Square/Circus/Place): “plein” in Dutch. Open area in built-up area. From Middle French “plain” from Latin “Planum” meaning surface or area. In Dutch evolved to open area in city. In Middle Dutch “plaetse” was used, here I do hear some Spanish influence “plaza”. (photo: Grote Markt Plein, Antwerp)

Singel: idem in Dutch, or circular/ring road or stadsgracht (city canal). Originally singel meant borderline. In Old French it means city enclosure. Ancient Dutch cities predominantly had canals to protect. Hence the Dutch synonym for city canal. (photo: Amsterdam Singel)

Alley(way): “steeg“, small (side) street. The word is literally derived from “stijgen“, to mount as the alleyways climbed up from the canals to the dike. Originally from rural areas but over time a more frequent name for small side streets in city or village. In Flanders also called “gang” as in hallway, passage or corridor. (photo: Vlaaikensgang, Antwerp)

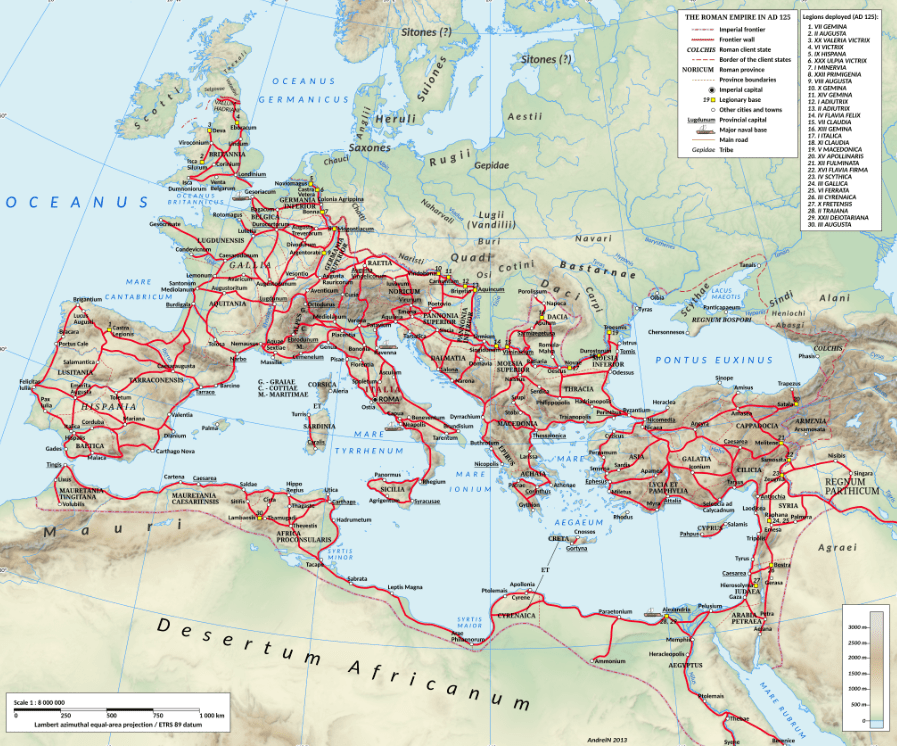

Street: paved way. Derived from Latin “via strate“. Conjugation of “sternere“: pave, spread and straighten. In the early days streetway was used but way was dropped. In Dutch we also say sea-street but then it is derived from English strait in the meaning of small passage. (Reigerstraat, Breda)

Way: “weg“, path or street. Origins are in Indo-European for riding/driving or transporting. In the Dutch “bewegen” (to move) includes “weg” for a reason. Hence the definition of route on which people travel.

I am actually quite happy with so many styles of ways. Except for motorways/freeways pedestrians can walk on all public ways. I would certainly advise against using Komoot as it sends cyclists and hikers over regional roads that are basically motorways. Legally cyclists and hikers are all allowed. Common sense however, which certain apps do not have, might send you over locally infamous death roads.

Also car dependency is not the way forward. If you want to live in the middle of nowhere, expect solitude.

Perhaps this little piece will show why European road network is what it is and not organized or well planned as in the US. Another reason is how European routes started as explained here.

It fascinates me that in English some definitions are regulated. And then again the Commonwealth uses “close” for cul-de-sac whilst US have dead ends. Funny how the English don’t translate the French word bottom o/t sack or Tolkien’s Bag End.

- Road (Rd.): Can be anything that connects two points. The most basic of the naming conventions.

- Way: A small side street off a road.

- Street (St.): A public way that has buildings on both sides of it. They run perpendicular to avenues.

- Avenue (Ave.): Also a public way that has buildings or trees on either side of it. They run perpendicular to streets.

- Boulevard (Blvd.): A very wide city street that has trees and vegetation on both sides of it. There’s also usually a median in the middle of boulevards.

- Lane (Ln.): A narrow road often found in a rural area. Basically, the opposite of a boulevard.

- Drive (Dr.): A long, winding road that has its route shaped by its environment, like a nearby lake or mountain.

- Terrace (Ter.): A street that follows the top of a slope.

- Place (Pl.): A road or street that has no throughway—or leads to a dead end.

- Court (Ct.): A road or street that ends in a circle or loop.

Of course, these are more guidelines than hard-and-fast rules, and not every city in the world follows these naming conventions exactly. Also, they tend not to be as strict with these in suburbs and newer areas: sometimes a street is called a “lane” simply because an urban planner or developer might think it sounds nice. (source: https://www.mid-americantitle.com/local-news/streets-ave-court)