In preparation of multiple day hiking trips I boarded a train. In the Lowlands we have a concept ‘treinstapper’, take the train to a certain destination, hike wherever you like (mainly parks and greenways – we call them “slow roads” as motorized vehicles are not allowed) and take the train back home. The word ‘treinstapper’ is self-explanatory since the Dutch language loaned ‘trein’ from English and ‘stapper’ entered the English language via Germanic influence.

Train has a fascinating etymology with different meanings over time.

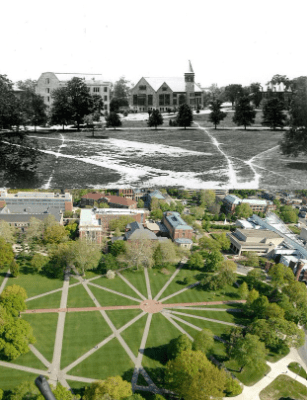

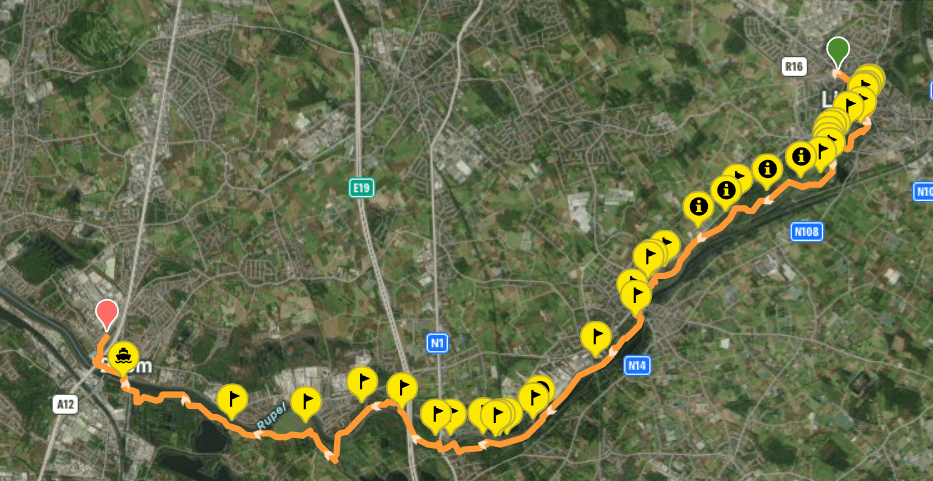

I believe it was my first visit to the Medieval city of Lier. The city is linked to (Belgian) Saint Gummarus. The red figure left of Lier is their nickname: sheep’s heads. If you want to know why, read here.

After military campaigns (and perhaps his wife) he had enough of humanity, I assume. The city grew up around his hermitage. Stories, legends, folk tales can be easily found on the www. Duke Henry 1 of Brabant granted Lier city rights in 1212. Thanks to textile industry many regions in the Lowlands boomed in 12th and 13th century. And then the 80 Years’ War happened, I know, a recurring theme and it was a temporary downfall for current Belgium and the Netherlands. Lier bounced back thanks to their cattle market, breweries and textile factories.

In 1580s English a lier-by was a mistress. Also no links to the word lyre (lyrical) derived from Latin Lyra which is also the Roman name given to the city.

A nationally renowned author and poet described Lier as “where three meandering Netes (river) tie a silver knot”. The Big Nete and Small Nete become the (Nether-)Nete.

I barely took any photos in the city as it was their annual November funfair. This one above is also pretty famous, the Zimmer tower with its many dials.

Next port of call is Duffel (yes, you do recognize it, don’t you).

Celtic presence might indicate that the town’s name was given by them, “Dubro” meaning water. Just like Lier, many artefacts were discovered but from times when writing was deemed not important or non-existent. Duffel got immortalized worldwide for the coarse woolen cloth. Or rather thanks to the English language. I don’t see anyone asking for a “duffeljas” (jacket) or duffeltas” (bag) in Dutch shops…

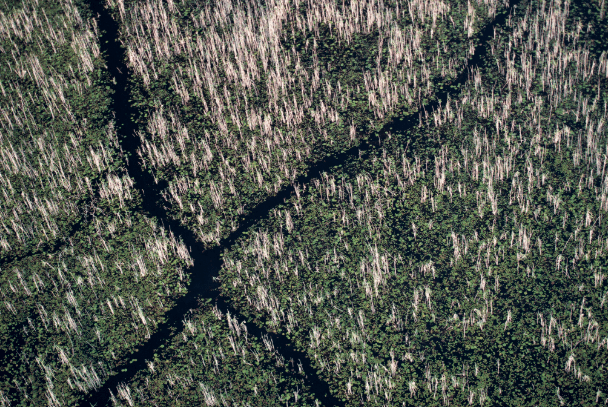

From the textile industry I venture into brickmaker’s territory. Obviously both requiring a continuous flow of water, the latter also needs clay. Does it surprise anyone that many fishing clubs are present? The many claypits have been repurposed as ponds and nature sites. Plenty of efforts were needed since – back in the day – the pits were used to dump all sorts of trash, including asbestos. The soil is still being monitored.

And last in line is Boom. Like Rumst, Boom is famous for its bricks. I have written about Boom here.

The hike was just over 15.5mi and I ended up crossing the river by ferry boat (notice similarities with the Dutch ‘veerboot’?). No, the verb to veer is from French. In Dutch we have adjusted veder to veer. In English the word transformed to feather. Neither feather nor veering is relevant. Language and its evolution can be rather confusing but it keeps me occupied on the road. The scenery was stunning though and many areas have been re-designated to flood plains.

In Belgium we have a saying: A Belgian is born with a brick in his stomache. Just to say everyone wants to build his or her own house. The brickmaker’s industry requires much less (human) manpower and plenty have found out – the hard way – that you simply cannot build wherever you want. A colorful history mixed with life lessons.

A truly fascinating region wedged between capital Brussels and Europe’s second largest port: Antwerp.

Additional pics and details: https://nl.wikiloc.com/routes-wandelen/ts-lier-duffel-boom-238811576

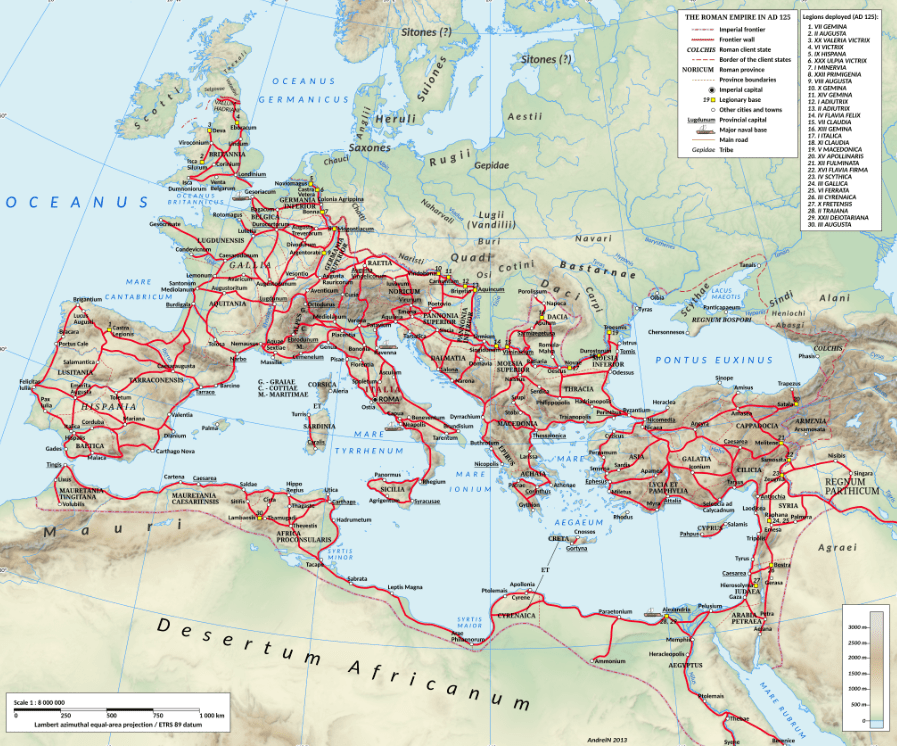

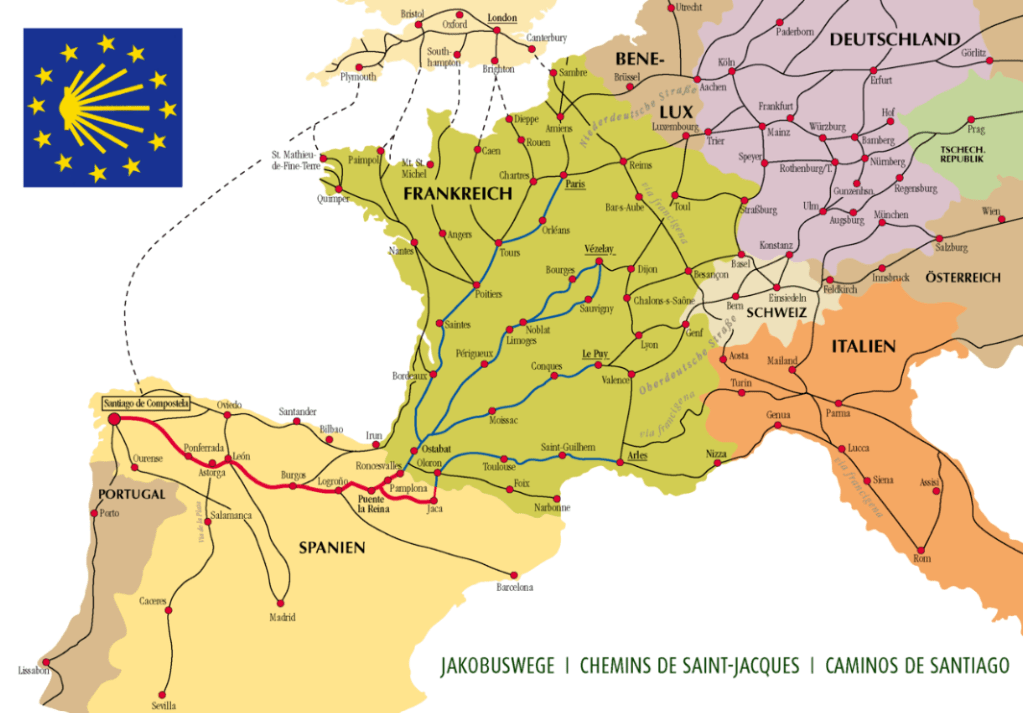

In case you want to walk the Camino, and opt for Via Brabantica, you will pass by this region (if you choose the original route and not a shortened version).